What can the COVID-19 Crisis Teach us About Preparing for Death?Strange times we are living in. And, as always, there is something to be learned in adversity. I am noticing that questions related to death and preparation for it are burbling to the surface for me and for other people right now. How did we get here? During the last century, in western settler cultures in particular, we have taken death largely out of our homes and away from our faith communities and handed it off to the experts. Medical folks, funeral directors, hospices, hospitals, long term care homes. This is where and how death is managed now. Consequently, we have lost skills. We don’t see or handle or anoint dead bodies anymore. Most of us don’t know what to do or how to be when sitting with a dying loved one or a woman who has just miscarried. No one modelled that for us, and we can’t model it for others. We often allow the professionals to mediate the experience for us. We don’t trust our instincts. No one is laid out in the front parlour anymore. Most of us don’t live on farms or hunt for our food so we are removed from the natural cycles of birth and death amongst animals. How do we experience death and dying now? Death is mostly an individual event in our lives and the lives of our families. It is less and less a community event. We speak in hushed tones. We don’t know much about how to move through grief or support others moving through it. The rituals and signposts of mourning are fading in our collective memories.

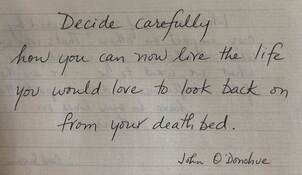

That is certainly how I felt witnessing the dying of my mother-in-law and my father a number of years ago. They did not seem prepared and I did not know what they wanted or how best to support them. Or even talk with them about what was going on. That felt empty and lonely and unsatisfying – as if I had somehow failed at something where no-one had explained the rules of the game to me. How is COVID-19 impacting this? Into this social context comes COVID-19. Suddenly pictures and statistics and warnings about death are taking up the entire media landscape. We get hour by hour updates on the number of deaths and detailed stories of how people died and the stresses on the people caring for them. It isn’t just the occasional life event that we stumble through now. We can’t escape it. Our fear and denial are harder to hide. Maybe this is an opportunity… How could we make this a positive thing? What if instead of allowing this to ratchet up our fear of death, and running from it, we turn around, face it, and allow ourselves to actually feel it and see where that takes us? What if that created opportunities to contemplate our own mortality, to make plans to guide our loved ones when our time comes, to think about our legacy and how we want to be remembered? What if we brought the idea of death into the light and turned that fear into positive action? What if we took some of this ‘found time’, now that our busy busy lives have been slowed down, to take control of some small things that we can. Like making a will or an advance care plan? Like telling stories about elders and ancestors to grandchildren? Like pre-paying for our funerals? Like writing our life story or love letters to unborn descendants? What if we actually did some of that? What might happen? Being more prepared can soften our fear What if taking control of some concrete actions actually softened our fear? What if it made us more mindful after this is all over? What if we had a clearer sense of what is most important in life? And allowed that to guide us in the days ahead? Death doulas witness this all the time with people who are near the end of their lives. Facing their fear and taking concrete steps to influence the kind of death and legacy they want really can soften people’s fear. It could help all of us right now. Because, while any single one of us is very unlikely to die from COVID-19, we will all die at some point. And so will everyone we love. We don’t know when or how. So why not take this time to be just a bit better prepared? Perhaps you will feel a little less afraid as a result. I know I felt better after letting my husband and grown children know that in the current circumstances, I would not want to be put on a ventilator if it came to that. I don’t want to burden them or the doctors with not knowing my wishes. I have already lived a full life and would rather a ventilator go to someone younger – that children lose a grandparent in this epidemic rather than a parent. Sharing my wishes with my loved ones is one action I have taken to be better prepared for my eventual death. What’s yours? CIRCLESPACE'S NEWEST FREE RESOURCE

Caring from Afar: Staying Connected and Saying Good-Bye During Physical Distancing How do we show our love when we can’t be there to hold a loved one who is ill? How do we accompany them through the dying process if we can’t be physically present? This resource offers 6 steps to comfort people who are separated from their ill or dying loved one. It includes ideas for how to stay connected and ways to honour your grief through these unprecedented times.

2 Comments

"What's your favorite thing about death?" was the first question I was asked by an earnest and inquisitive student. Whoa! Way to get things started!

This past week I had the privilege of being interviewed by a group of university students at an event called Campus Conversations, organized by Christopher Bowers, multi-faith co-Chaplain at the University of Victoria. It was a truly delightful opportunity for me to talk about my profession and to reflect on why I love this work! It was also amazing insight in to how this group of post-millenials view their relationship to death and the supports they need to accept the reality of their mortality. Several students approached me after the interview with further questions and comments. The theme that came up the most: My grandparent recently died, how can I support my parents through their loss? We talked about being direct and honest, saying things like, "I don't know what to say but I want you to know I see how much this hurt. I'm here for you. How can I help?" We talked about setting up a weekly phone call with their mum back home, so they can look forward to a regular, loving connection. And we talked about the importance of seeking grief support, even years after the death of a loved one. Finally, the piece that surprised these students the most: we talked about the importance of sharing their own grief; for a death in the family is an opportunity to explore their own relationship to death and to put plans in place for themselves. (I'm sure you've heard me say this before, if you're 19 years old or older, you need to make an Advance Care Plan that defines the care you would want if you couldn't make decisions for yourself!). These young people expressed so feverently their desire to be there for their parents. Their love and loyalty was incredibly touching. For me, this reinforced my belief that many of us are seeking more authentic connections and a relationship to death. But, sadly many of us aren't yet equipped for it. As my friend, counsellor Shauna Janz says, grief is a learned skill. So, too, is dying. I felt energized and even more committed to my work as an end-of-life planner and death doula after this interview. I hope this video inspires you, too! Campus Conversations: Chelsea Peddle... Death Doula Chelsea Peddle is an end-of-life planner and death doula. In 2017, she founded CircleSpace: Empowered End-of-Life Planning in Victoria, BC, to help people prepare for end-of-life so they can live in peace. Through workshops and coaching, Chelsea offers emotional, physical, spiritual and pragmatic support for individuals and their families. Chelsea recently expanded her services to offer death doula care: guiding and companioning people and their families before, during and after death. Chelsea's passion is helping people find peace of mind and peace of heart in a time of great stress. She has an End-of-Life Doula certificate from Douglas College and is a member of the End-of-Life Doula Association of Canada.  You can’t take it with you, so why do we make those impulse buys this time of year? The talking unicorn you’ll want to smash within 5 minutes of inserting its batteries. The novelty back scratcher. The wind-up robot and stockings-full of plastic dollar store wares. Are we seeking connection? A moment of shared indulgence? Are we pacifying our fear of being unliked by buying more and more? If you’re like me, the answer is sadly, “Yes.” In Dr. Phil’s words, “How’s that working for you?” Do you feel connected and loved? Are you living your values? Are you caring for your family and our planet? Are you getting what you really want and need? Likely, not. During my annual pre-Christmas clean up, I recently took 3 bags of long forgotten toys to the donation bin and 2 more bursting with broken things to the dump. As I tossed the bags down the chute I wondered, how many of these items were meant to show my love on Christmas days past? The cost to the planet became crystal clear as my bags tumbled down, landing on other obsolete demonstrations of "love"; the cost to my relationships: a hollow feeling in my chest. I know consumerism doesn’t bring connection; you know you can’t buy love. So, why is it so hard to change? Perhaps it’s because this holiday season and our desire to consume is tightly wrapped in our culture of death denial. Writer Philip Roth says, “In every calm and reasonable person there is a hidden second person scared witless about death.” And boy, do we humans work hard to quell the petrified voice of that second being. It makes sense that shopping appears to be the perfect antidote to death. First, you feel that lovely hit of serotonin when you lay out your debit card for something shiny and new. We literally feel “love,” thanks to the hormone surge. A base need seems to be met. Sheldon Solomon, one of the founders of terror management theory, suggests our purchase then becomes a symbol of immortality; something intended to last longer than we do, thereby helping us to conquer death. For a moment, our death anxiety is quieted. But in our world of planned obsolescence, these material symbols are fragile and their effects fleeting. They break or fall out of favour and are soon cast aside, speeding the destruction of the planet and leaving a void in our relationships. Awareness of our mortality creeps back in to our psyche. To keep our existential anxiety at bay (and to demonstrate our love), we must buy again, and again and again. Our search for immortality is not inherently a bad thing. We just need to seek it in the right places (and perhaps become more aware of the false promises of consumerism). Being mindful about our desire to be a part of something bigger and longer-lasting than ourselves can move us in a productive direction. One that can enrich our lives now and soften our loved ones’ grief, later. So, here’s my challenge for you this holiday season: As you go about your holiday shopping this year, IMAGINE THIS IS YOUR LAST CHRISTMAS, HANUKKAH OR WINTER SOLSTICE. How do you want your loved ones to remember this time with you? Is there a family heirloom or special object you’d like them to enjoy now? Are there things unsaid? Love to express? Wisdom to pass down? Next year, when they look back on this time, will your loved ones still be cherishing your gifts, or will these gifts have already faded in to the past? Invest in experiences. Give the present of your presence and undivided attention. Gift a love letter to your beloveds. Don’t turn away from death this season. Let it inspire you and guide you to true immortality through genuine connection and love. With gratitude, Chelsea |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed